Since the financial crisis, stress tests have become an important tool for surveillance and financial stability (Constâncio 2017). In this context, an important question is whether stress testing contributes to financial stability by promoting risk reduction in the banking sector, as recent evidence suggests (Cortes et al. 2017, Acharya et al. 2018, Steri and Pierret 2018). Stress tests provide in-depth insight into bank vulnerabilities to supervisors and the public through an intense supervision process. Recent evidence suggests that prudential supervision decreases the risk-taking activities of banks (Rezende and Wu 2014, Hirtle et al. 2018, Bonfim et al. 2018, Kandrac and Schlusche 2019). Similarly, in a recent study, we show that tighter prudential supervision led to a disciplining effect for banks in the context of the Authority’s EU-wide stress test. European Bank (EBA) led by the ECB in 2016.

How prudential supervision is exercised in stress tests

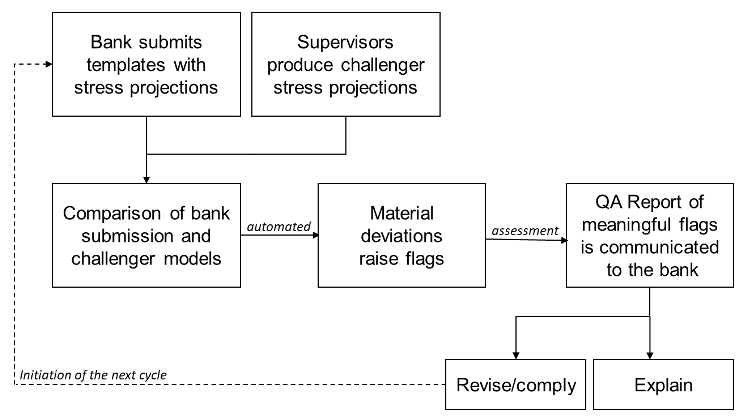

In Europe, stress testing involves interactions between banks and supervisors on bank risk management practices as well as confidential communications on best practice and stress testing techniques. We use data on these confidential interactions to assess the degree of control over Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM) banks under the direct supervision of the ECB in the 2016 EU-wide stress test. These interactions occur as part of the constrained bottom-up approach pursued in the exercises coordinated by the ABE (see Figure 1). In this context, banks use their own internal models to generate projections (eg for credit losses). Meanwhile, bank projections are challenged by relevant supervisors, usually by applying top-down models and other challenger tools. In the presence of significant differences between these two series of projections, “flags†are set off and are then discussed between the supervisory authorities and the banks. Banks must comply or explain issues raised in interactions with the ECB. We construct the control measure by counting indicators related to credit risk projections. Intuitively, banks that received more reports had to work harder on their new submissions and had longer and possibly more intense interactions with supervisors, while banks that did not receive any reports in principle did not. had no other interaction with the controllers.

Figure 1 Simplified illustration of a quality assurance cycle under the constrained bottom-up approach

Source: Personal illustration based on Mirza and Zochowski (2017).

Scrutiny measures the intensity of stress tests

We apply a differences-in-differences approach where we use the stress test as the treatment and the scrutiny involved as a measure of the intensity of the treatment. In a first step, we compare the credit risk of the banks that participated in the stress test and of the banks that did not participate in the stress test four quarters before and four quarters after the 2016 stress test. Secondly, we compare the risk of banks which have been subject to more intense prudential supervision and of banks which have received less or none at all.1 The 2016 EU-wide stress test was performed on Important Institutions (SIs). Less significant institutions (LSIs) have not been tested and therefore we use them as a control group.2

The effect of prudential supervision on credit risk

We focus our analysis on credit risk, which accounts for a large portion of stress test projections and on average 86% of risk exposure amounts on bank balance sheets. To measure bank-level credit risk, we use Risk Weight Density (RWD), which is the aggregate risk weight assigned to total credit risk exposures according to regulatory standards.

Figure 2 Estimate and 90% confidence interval of the differential effect on RWD between tested and untested banks before and after the reported quarter.

We find no significant difference in RWD between the treatment group and the control group before the stress test (2015q1 and 2015q4; see Figure 2) but significant negative differences for the period after the test (2017q1 to 2017q4). The reduction in RWDs of tested banks after the stress test was on average 4.2 percentage points lower than the reduction of untested banks. This effect is economically important because it is equivalent to about a 20% change in the standard deviation of RWD.3 These results confirm findings based on US data that “treating†banks with stress tests can affect their risk.

figure 3 Marginal effect and mean effect estimates with 90% confidence intervals of the differential effect of examination intensity on RWD

Second, we show that the more interactions banks have with supervisors, the greater their RWD reduction after the stress test exercise (see Figure 3). We find that banks that have undergone further scrutiny (the half whose scrutiny intensity is greater than the median) have a decrease in credit risk of 5.6 percentage points greater than that of the half that was less examined.4 Overall, these results provide new evidence that the tighter and more intrusive prudential supervision coupled with EU-wide stress testing has the potential to improve the risk management practices of banks and companies. induce a lower banking risk.

Political implications

We contribute to new evidence of the effectiveness of prudential supervision. Our results suggest that stress tests conducted by applying robust quality assurance to bank projections and models have disciplinary effects on the risk of tested banks. However, it is clear that one of the main objectives of stress tests is to correctly assess the risk profiles of banks. Our results do not provide information on how this goal is achieved. The possible strategic underreporting of bank vulnerabilities under a bottom-up approach could undermine the reliability of stress test results from this perspective (Niepmann and Stebunovs 2018). Pursuing a more impartial top-down approach while maintaining supervisory interactions with banks during and after the stress test may be more appropriate to achieve this goal. Therefore, with our analysis, we are only providing one glimpse among many that could serve the political debate on the future design of stress testing in Europe.

The references

Acharya, V, A Berger and R Raluca (2018), “Lending Implications of US Bank Stress Tests: Costs or Benefits? “, Journal of financial intermediation 34: 58-90.

Bonfim, D, G Cerqueiro, H Degryse and S Ongena (2020), “On-site inspection of zombie loans», CEPR Working Document No. 14754.

Constâncio, V (2017), “Macroprudential stress tests: a new analytical toolâ€, VoxEU.org, February 22.

Cortés, K, Y Demyanyk, L Li, E Lutskina and PE Strahan (2020), “Stress tests and loans to small businessesâ€, Financial economics journal 136 (1): 260-279.

ECB (2019), “What makes a bank important?», European Central Bank Banking Supervision.

Hirtle, B, A Kovner and M Plosser (2020), “The Impact of Supervision on Bank Performanceâ€, The Finance Journal 75 (5): 2765-2808.

Ivanov, I and J Wang (2019), “The impact of bank supervision on corporate creditâ€, Working Paper.

Kandrac, J and B Schlusche (2017), “The Effect of Banking Supervision on Risk Taking: Evidence from a Natural Experienceâ€, Financial and Economic Discussion Series No. 79, Board of Governors of the Federal reserve system.

Kok, C, C Müller, S Ongena and C Pancaro (2021), “The disciplinary effect of prudential supervision in the EU-wide stress test», CEPR Working Document No. 16157.

Mirza, H and D Zochowski (2017), “Quality Assurance in Stress Tests from a Top Down Perspectiveâ€, Macroprudential Bulletin 3.

Niepmann, F and V Stebunovs (2018), “How EU banks modeled their stress away in the 2016 EBA stress testsâ€, VoxEU.org, July 30.

Pierret, D and R Steri (2019), “Stressed Banksâ€, Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper n ° 58.

Rezende, M and J Wu (2014), “The effects of supervision on bank performance: Evidence from discontinuous exam communitiesâ€, Midwest Finance Association 2013 Annual Meeting Paper.

End Notes

1 We also compare the banks that received more treatment to banks that received less treatment, excluding banks that received no treatment, i.e. the effect of prudential supervision within banks tested.

2 Significant institutions are SSM banks that meet certain criteria (ECB 2019). LSIs are SSM banks that do not meet any of the criteria. EMIs are directly supervised by the competent national authorities under the supervision of the ECB, which guarantees the consistency of the regulatory framework and supervisory practices applied to these banks. To account for the differences between SI and LSI, we include robustness checks where we use sample matching and exclusions to estimate the effect in a sample with minimized differences.

3 The average RWD of the banks tested prior to the stress test is 43.7 percentage points with a standard deviation of 22.5 percentage points.

4 A 10% increase in the intensity of prudential supervision decreases the RWD on average by about 0.27 percentage points.